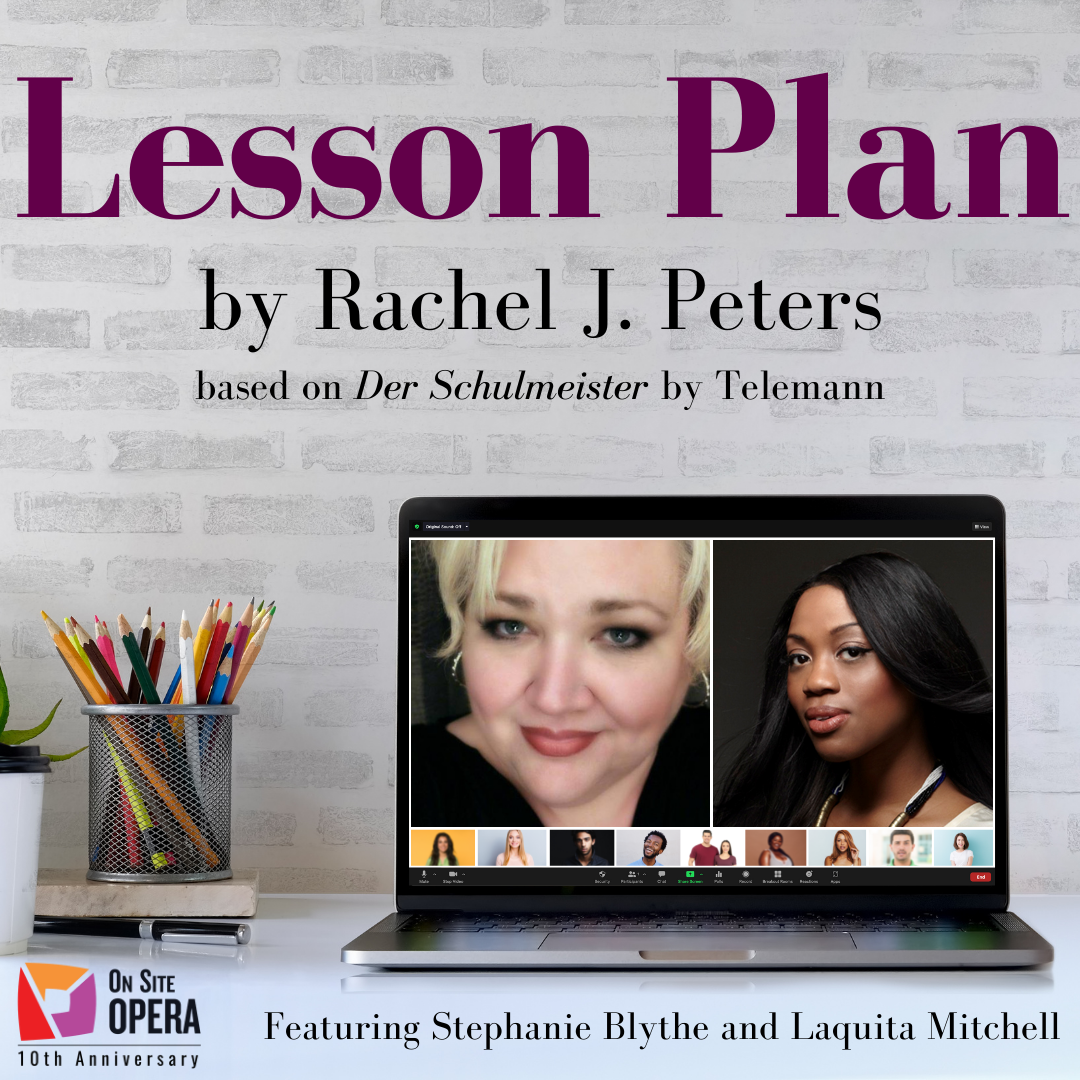

LESSON PLAN Stars Stephanie Blythe & Laquita Mitchell

Happy World Opera Day 2021, everyone! Opera is not only still happening but flourishing despite an ongoing pandemic and so many other forms of madness. And I’ve got a humdinger of an operatic tale to share this year. Buckle up:

One day during my high school years, I was browsing in a Borders (remember those?) and came upon an astrology book detailing the characteristics of those born on each day of the year. Under my own birthdate, it said, “Being you is like sitting on a volcano.” I don’t pay too much attention to astrology, but I’d say that’s generally an accurate assessment. For most of this year, I have been sitting on the best possible kind of volcano. I’m quite happy to scoot from that perch now that it can be told: On Site Opera has commissioned me to write a new work adapted and expanded from Telemann’s Der Schulmeister…for none other than Stephanie Blythe and Laquita Mitchell!

Several presidential administrations and chapters of my life ago, I was in the audience at the Met Opera, seeing a production which I honestly did not care about very much…until Stephanie showed up onstage shortly before intermission. I could not wait for her to appear again, and I have been a devoted fan ever since. If you had told me then that in 2021, I would eventually get to write something for her, I would certainly have laughed in your face in utter disbelief. But as we know, 2021 has brought plenty of surprises; most of them, however, are not the realization of such positive dreams as this!

The directive from Eric Einhorn, who leads the charge at On Site Opera, in a nutshell, was as follows: adapt Telemann’s existing 17-minute cantata for baritone and children’s chorus into about a 30-minute piece, providing a new English translation and adding a new character who is a foil to the music teacher. (You can learn more nerdy details about the original work and its surrounding circumstances here.) And it should be interactive, so that the audience logging in from home acts as the chorus. Also, there is a second source to factor in: a certain digital subscription series full of celebrity-expert-led (ahem) masterclasses.

Piece of cake, right? A charming little lark. On its face, perhaps. But if you know me, I’m a deep diver down rabbit holes full of non sequiturs, chasing butterflies and mixing metaphors rather questionably as I go. So here’s how I arrived at what became Lesson Plan:

First, this was my maiden voyage into singing translation. I was an avid speaker of German in my younger days (language immersion summer camp and everything), but I had to dust off a few brain cobwebs. Somehow I’d managed to convince Eric to let me try, and two pages of text was exactly the right bite-size assignment for me in this case. It was so much fun, particularly the challenge of preserving the original rhyme scheme but applying it to a contemporary setting. (I would love to do more of this in the future, just saying.)

But before I could even get that far, there was a lot more to discover about what I actually needed to say. So next, I purchased a subscription to the aforementioned series and watched so many hours of various musicians from all genres offering their widely varying philosophies and approaches to composition, performance, etc. Some of it was enlightening; even more of it was frustrating. Plus, besides the actual advice, there was the overall format of the series to consider: the structure of the videos, the visual layout, and what impressed me as a fairly passive version of interactivity. How on earth was this going to jive with the source material, and how could it be an operatic experience? Moreover, what was the point of view? Plenty of trained musicians had not-so-kind online responses to one particular set of these classes by a featured composer whose delivery style was amazingly consistent with Telemann’s Schulmeister character: bombastic and extremely self-assured, and not graciously so. And, since the Four Seasons Total Landscaping scheduling debacle lingered in recent memory, I thought it might be funny if a similar administrative misunderstanding landed our snobby protagonist in a decidedly non-top-conservatory environment. After some research, I’d settled on a fictional community college in the very real Middletown, Indiana. The tone of the piece would recall Waiting for Guffman. It seemed like a no-brainer, right down to this item sold at the Middletown Historical Society shop. If I could do just my job properly, hilarity was sure to ensue.

And then a few things happened.

Beyond my community of #newmusictwitter peers, I found many effusively positive reviews of this composer’s offerings. Viewers who were not professional musicians found the content not just fulfilling but life-changing; they came away with a much deeper appreciation of the way music supported storytelling and the craft of composition. And in a time where so many folks go out of their way to make noise about the [perceived] worthlessness of art and artists, that’s categorically a win for all of us.

Not long afterward, Eric confirmed that Stephanie had signed on to the project. I couldn’t believe my good fortune. I’d been poking around on YouTube for recent recordings of masterclasses with opera singers I respected and had made copious notes. We’re all very lucky that Stephanie has given many that have been recorded for posterity. She’s constantly doling out pearls of wisdom like they’re nothing at all, but this one stopped me in my tracks and made me gasp:

“We have to think about our voices as being part of the universe. It’s scientific, my friends. Nothing around us is in any kind of stasis. Air is moving around us, molecules are jamming into each other, there’s lots of energy moving around all the time. So when we start to sing, we just simply jump into the vibration and the movement that is already happening….When we pressurize our voices and then we let it go, it goes against nature. It’s not scientific. Let’s be soulful and scientific at the same time.”

Here I should say that right out of college, I attempted to be an operatic coloratura for a few years until I could admit that I was just not cut out for it, and that I would be better off writing the things I wanted to see onstage instead of wasting everyone’s time and oxygen lamenting the lack thereof. While I am certain I chose the right path in the long run, I did come into the commission carrying some baggage on this topic, and its bellhop was quite punctual.

Telemann’s Schulmeister isn’t a terribly multidimensional character: he’s pretty consistently grumpy in C major in 4/4 time for the better part of 17 minutes. But then there is this beautiful couplet in the finale:

Ein schönes Lied von rechten Meistern,

Kann Herze, Leib und Seel' begeistern

To quote Stephen Sondheim out of context (as I often do), “That’s what it’s really about, isn’t it?” Why would anyone ever embark on such a steep uphill climb, as teachers or students of music, without enduring faith in the absolute truth of this statement? I recalled those enthusiastic responses to the online masterclasses, and everything I’d observed over decades as a student and erstwhile teacher of music, and chewed on it all some more.

At that point, I finally got to speak with Stephanie on Zoom. I told her I hoped to make a meaningful goof for her, one that would be worth her time working with an unknown like me. In the 90 minutes that followed, she squeezed in so much perspective on her career as an artist and educator, and what we might find most compelling that was related to this source material. Thanks to her guidance, our Schulmeister found the form of Alice Tommasso, an internationally renowned contralto who considers teaching beneath her until she bumps up against some uncomfortable truths, including an extremely uninvited guest.

Soon afterward, my dear friend and collaborator of nearly 25 years, the lovely pianist Adam Marks, died suddenly. I have written much more in a previous blog post about what Adam’s friendship and musicianship will always mean to me. He did not know I had begun working on this piece. (Strangely enough, I recently learned that he was working out a time to play collaboratively for a coaching with Stephanie shortly before his death. It is an astonishingly small world.) I had always thought of Adam as mine, in my tiny corner of the music-making universe. But attending his funeral and reading the outpouring of love on social media from his many collaborators around the globe showed me that, through his activities as a musician as an upstanding citizen of the world, he belonged to everyone.

That’s what it’s really about, isn’t it? If so, how would my hardened cynicism serve a story like this? It wouldn’t. For Adam, to whom this new work is officially dedicated, and for everyone else, I needed to find another way to proceed.

That other way came with further exploration of the history of Middletown, Indiana. Having now spent an equal number of years as a kid in Missouri (where I’d participated in a wide range of musical pursuits from Guffmanesque to top-notch) and as an adult in NYC (with an eight-year intermission in the Boston area), I will never be convinced that a) New York is the center of the universe/the only place good music happens, OR that b) the Midwest is a sweet, quaint breadbasket of Americana without its own distinct challenges, heartaches, and brutal tensions. There is an oft-produced play about the town, which I saw, but my gut told me there was still more to the story. I was correct—history was on my side. A famous study of Middletown began in 1924 and re-upped every so often in the decades following…which also did not tell the whole truth and was, in fact, designed not to tell the whole truth. Luckily, Ball State University has many more resources on the subject, including an amazingly robust archive of oral histories. And there is an incisive five-part documentary about Middletown, some of which is available to rent now, though it was deemed too scandalous to air on TV at the time it was made.

This may all seem heady and excessive for a brief comic piece, but truth and humor tend to reveal themselves in equal measure whenever I poke around like this. And so I pieced together the story of Robinetta, an arts administrator at the local community college and an amateur chorus director in her off hours, who must pull off the Herculean task of making Alice’s class run smoothly. How fortunate to have the phenomenally talented soprano Laquita Mitchell originating the role of Robinetta. (I’m pretty sure I’ll never have access to this much operatic royalty in one place ever again, but life is allegedly long, so here’s hoping.) I was further inspired by conversation with Laquita, as well as several talks of hers that I found online. Her stylisitc versatility, which I admire so much, will be on full display here! Both she and Stephanie have spoken at length about the signifance of their respective experiences in productions of Aida. The sum of their insight brought me to the most important stop in the process: really, really, really sitting with what opera folks call the standard repertoire.

While I would not presume to speak for any other female composers—we are not a monolith, after all—I have a hunch that I’m not the only one of us with a complicated relationship to the Euro/phallocentric operatic canon. We are taught right out of the gate that it is everything to which we should aspire and everything to which our work will forever be compared regardless of actual intent, yet we should never expect acceptance into it. At various points in my career, I have fussed publicly about rejecting this ongoing comparison, sometimes perhaps at my own professional peril. But the canon is in Alice’s bloodstream and in the real-life bloodstreams of our two magnificent singers. And in mine. It would be foolish and detrimental to this project to pretend otherwise. I’d been awarded a composing residency to work on Lesson Plan in a repurposed church in rural Pennsylvania. As the snake who was also in residence snacked on the rodents upstairs, I had the luxury of some time to sit on a covered porch, watch the sunset, and listen to “the warhorses” over and over and over again. And eat a little crow, and cry more than a few tears (perhaps not unlike Corky St. Clair once did in his Blaine, MO bathtub), and write.

I do believe this Verdi fellow has a very bright future ahead of him.

But you guys! I swear there are jokes! As many as I can pack into what ended up being about 45 minutes! You don’t have to know much about opera…or cats (Wait, cats? What, did I say cats? What could that possibly mean?) to have a satisfying time with Laquita and Stephanie. You get to sing along with these masters of their craft! It’s been emotional, yes, but the overwhelming majority of that emotion is joy! There are six chances to take part on a device near you, beginning January 21st. Performance details are in my Events Calendar, and you can click below for more information as well. Happy, Happy World Opera Day indeed.